Instructions for Use (IFU)

Instructions for use (IFU) are essentially the user manual for a medical device, providing information such as:

- How to use the device

- Why and when the device should be used

- Technical specifications

- Maintenance requirements

- Troubleshooting information

- Cautionary or risk-related information

Manufacturers have a responsibility to design effective documentation to ensure safe use of their devices. People who fail to refer to instructions may overlook important warnings, which can result in unsafe device use. Further, when something inevitably goes wrong—accidents and litigation happen—the IFU is often the manufacturer’s first line of defense.

The IFU is part of the medical device user interface (UI). The UI includes packaging, website, customer support, and also, the IFU. The FDA mandates that labeling must be provided with certain types of medical devices (21 CFR Part 801, n.d.).

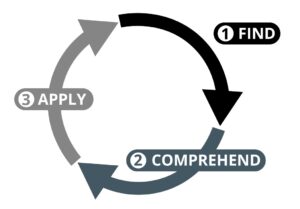

A model of IFU usage

For people to make proper use of IFUs they first need to be able to find the appropriate information. Second, they need to comprehend that information in order to make use of it. Finally, they need to be able to apply that information to the task at hand.

Advice for complying with FDA

Here is some advice for complying with FDA instructions for medical device use that are useful, usable, and desirable:

Start designing IFUs early

IFU design takes time. Do not short-change this process. Design them in tandem with the device itself. This ensures that the writing is not done at the last moment. It also keeps track of when the device is becoming too difficult to use. If understanding the device requires an extensively detailed and complicated IFU, then the device design may need to be addressed.

Develop a comprehensive user profile

According to FDA, instructions for the use of medical devices must be designed for a range of users, uses, and environments. Start by identifying all end-users (primary users, secondary users, rare users such as maintenance technicians, etc.) and develop profiles by understanding the scope of their needs, capabilities, and limitations.

Pay special attention to devices developed for lay users. Instructions for lay users need to employ non-technical language that is easy to understand. Part of the FDA’s oversight of medical devices is to ensure content created for lay users can accommodate at least a fourth- to fifth-grade reading level and no higher than an eighth-grade reading level.

Develop a strong environmental profile

IFU use is impacted by environmental elements such as lighting, temperature, humidity, space, noise, distractions, and access to technical support. Oftentimes, IFU formats are not conducive to their use environment. For example, paper-based instructions for technicians who reprocess endoscopes are not useful because they work in wet environments and are therefore not likely to reference the IFU at the point of use.

Consider the user’s tasks

Conduct a task analysis to identify the steps to use the device as intended. Then, consider the larger use scenarios. Will the user need to rely on the IFU during each use of the device? Will the IFU only be used as an adjunct to training? Where will the IFU likely be stored once it has been received? Will a user refer to the IFU during a crisis? Answering these questions will provide insights and further define the requirements of the IFU design inputs.

Make IFUs as simple as possible

Albert Einstein pointed out that everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler. So it is with IFUs, which can be too long, wordy, and detailed. This adds visual noise to the document, making it difficult to locate specific information. Every piece of information must be examined critically to determine if it should be included.

Each additional piece of information may make some other piece of information more difficult to find. For example, we have observed many IFUs that list all the warnings and cautions before the user even gets to the first step. Given that a user is unlikely to remember the first warning out of a list of 15 by the time they get to the relevant step in the IFU, this approach is not helpful at all.

Make it easy to find information

People look for information by paging through the document, skimming high-level phrases, conducting keyword searches, recalling where they have seen the information before, or guessing its location based on their current mental model. With any luck, and with good design, people recognize the content they are searching for.

Organization

Good organization makes information easier to locate, providing the reader with clues that enable them to make educated guesses when looking for it. Categorization is king here. People tend to look for the category first, followed by the specific item. Since items within a category are more related to each other than items in different categories, careful organization will guide the user, like breadcrumbs, to the information they need.

Three simple rules to smart categorization:

- put related information closely together

- separate that information from unrelated information using blank space (aka “whitespace”), or borders

- indicate the categorical hierarchies using consistent headers, font size, font weight, font capitalization, or indentation

Consistently presenting content enables users to predict the location of, and immediately access, information. Consistency also enables users to learn rules once and apply them repeatedly.

To adhere to the first rule, place images adjacent to its related text, and do the same for warnings and cautions. Do not place warnings and other cautionary information ad nauseum at the beginning of the IFU, where readers will either ignore it or forget it by the time it is needed.

Help people understand

Once users have found the information, they need to learn and understand that information. Being concise helps simplify instructions. We have experienced too many IFUs that are lengthy due to repetitive information. To be concise in procedural tasks, begin sentences with an action verb. For example, instead of writing, “The connector cap should be attached,” write, “Attach the connector cap.”

Help people apply the information

Finally, people must be able to use the information to conduct some task or activity with the device. Often, simply understanding the information is not enough—people need support while they do the task.

This might entail working with the device while simultaneously referring to the open IFU. Sometimes people cannot remember the exact steps required to complete a task without having instructions in front of them. Other times, users may not be able to review the IFU while using the device. In either situation, there are several ways to support this activity of applying information.

Instructions should be arranged into tasks and subtasks and should be outlined with numbers or bullets. Steps that need to be carried out in serial order should be outlined using sequential numbers, and bullets should be used when starting or introducing information. Using numbers for sequential steps will help to ensure instructions are applied in the correct order.

Provide information about what users should expect to see, hear, and feel when they do something correctly. Use descriptive language of visual, tactile, and auditory feedback cues. A visual example would be, “Ensure there is no gap between the cap and the tip of the device.”

An auditory example would be, “Listen for the beep to signal that the task is complete.” A tactile example might be, “Insert the device until it clicks into place.” Including feedback not only allows users to check their work, but ensures that they are aware of their progress in using the device.

Consider the regulatory requirements

Before you begin developing the IFU content, make sure you understand the regulatory requirements as well as non-regulated industry standards for your device. For example, in the United States, the FDA governs the labeling of medical devices.

Regulations for developing IFUs or “labeling” for medical devices can be found in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), and are specifically covered in 21 CFR 801.1–801.437. Thus, 21 CFR 801.1–801.437 are mandatory requirements. In the U.S., there are several documents published by the FDA that provide guidance for developing and evaluating medical device labeling. The guidance documents include, but are not limited to:

- Guidance on Medical Device Patient Labeling; Final Guidance for Industry and FDA Reviewers (CDRH, 2001)

- Guidance for Industry: Label Comprehension Studies for Nonprescription Drug Products (CDER, 2010)

- Labeling Regulatory Requirements for Medical Devices (CDRH, 1989)

- Guidance for Industry and FDA on Alternative to Certain Prescription Device Labeling Requirements (CDRH, 2001).

Perhaps the most important industry standard to adhere to when developing IFU content for medical devices is the ANSI/AAMI HE75-2009: Human Factors Engineering—Design of Medical Devices. This standard provides comprehensive guidance for designing IFUs for diverse populations and environments.

We hope this overview for developing IFUs has helped demystify the process and made it more achievable for your next project. Even so, given the multitude of guidelines and regulations that need to be followed and addressed, it is well worth it to bring on human factors experts who can review your IFU content and ensure it meets FDA standards.

Contact us to learn how we can help you with your FDA instructions for medical device use that will pass FDA oversight of medical devices.