In the world of medical devices, clear and effective instructions can mean the difference between life and death. They can also be the key to achieving optimal rather than merely adequate performance, or worse, errorful performance. As human factors professionals, we constantly strive to optimize the interaction between humans and systems. But what if a single word in our instructions could influence the performance and learning speed of a task? This question lies at the heart of attentional focus research, a body of work that has been reshaping our understanding of motor skills for over two decades.

Current Practices in Human Factors

One aim of human factors is optimizing the interaction between humans and systems. Designing intuitive and effective instructions is one method that can be used to achieve this goal. Instructions for use (IFUs) are critical for ensuring that healthcare professionals and patients can operate devices safely and effectively. These instructions typically focus on clarity, conciseness, and usability, but rarely consider the attentional focus of the user.

Most IFUs emphasize step-by-step procedures and safety warnings. This can inadvertently direct the user’s attention internally (their own mechanics, for example) rather than the desired outcome. Consider an example in the context of surgical robotic systems. The surgeon might be instructed to “rotate your hand and wrist counterclockwise” to understand the system’s limit and achieve the proper angle for a suture. This instruction directs the surgeon internally to their own body parts and mechanics. An alternative instruction could be “rotate the instrument counterclockwise” directing their focus externally to the desired effect of the movement. But does this subtle change in instruction really have an effect?

The Power of Attentional Focus

Attentional focus refers to where an individual directs their attention while performing a task. This focus can be internal (concentrating on one’s own movements and body parts), or external (concentrating on the goal of the task or the effects of the movement on the environment). Research has consistently shown that these different types of focus can significantly impact the performance of a task as well as the speed at which the task is acquired or learned.

Instructions promoting an internal focus can constrain the user, leading to a decrease in task performance and slowing the rate at which they learn, particularly in high-stress medical environments where efficient and accurate device usage is paramount. Instructions significantly influence how users direct their attention, which in turn affects their performance on the task at hand.

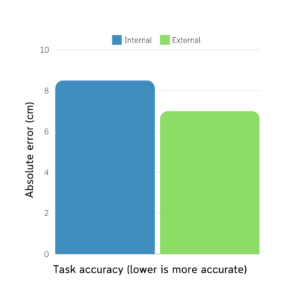

The effects of internal focus of attention are well-documented. In a study investigating the effects of instructions on dart-throwing by Lohse et al. (2010), participants who focused externally on the flight of a dart performed more accurate dart throws compared to those who focused internally on their arm movements. Additionally, there was reduced muscle activity in the triceps during the external instructions, relative to the internal instructions. This study demonstrated that external instructions led to superior task performance and more efficient movement.

These findings have been replicated in dozens of well-designed studies for a wide range of tasks in various contexts. While much of this research has been conducted in exercise or sport science, this effect is not limited to sport. If users are performing a task or interacting with a device, an emphasis on the instructions they receive should be made as it can have a strong and immediate influence on their performance.

To explain this effect, Wulf et al. (2001) proposed the Constrained Action Hypothesis, suggesting that an external focus of attention promotes automatic control processes, leading to more efficient and effective motor performance. Conversely, an internal focus systemically “constrains” the user, hindering them behaviorally, cognitively, physiologically, and biochemically. Dozens of studies have supported this hypothesis across various domains, including medical contexts, rehabilitation, and everyday tasks (Chua et al., 2021).

The Single Word Effect

The attentional focus effect is so strong that research has shown a single word can instantaneously influence how we behave. The evidence overwhelmingly supports that an external attentional focus, compared to an internal one, leads to better task performance outcomes, such as greater accuracy, faster reaction times, and increased force production. It also enhances task efficiency, including improved neuromuscular efficiency, more effective neural strategies, and the production of movement mechanics similar to those of skilled individuals (An & Wulf, 2024).

Not only do instructions that direct attention externally enhance the performance of a task, instructions that promote an internal focus have been shown to hinder task performance relative to neutral instructions (e.g., “do your best”) or no instructions at all. For example, Strick et al. (2024) compared multiple types of internal instructions on performance during a long jumping task. This study demonstrated that all internal focus conditions led to worse performance compared to the control condition (“do your best”). This indicates that internal focus instructions can hinder task performance even when compared to neutral instructions. In other words, while good instructions are necessary to optimize the performance of a task, poor instructions can be worse than no instructions at all.

Generalizability of Attentional Focus Effects

The benefits of attentional focus are not confined to specific tasks or populations. Research has demonstrated that external focus enhances performance and learning of motor skills across a wide range of contexts. This effect is evident for both simple and complex tasks. This makes it applicable to a variety of activities from basic movements to intricate skills. Furthermore, the advantages of external focus extend to both novice and highly skilled individuals, indicating its broad applicability regardless of expertise level.

Attentional focus strategies have also been shown to benefit neurologically healthy individuals as well as those with impairments. This includes patients recovering from strokes or dealing with neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease. Additionally, the positive effects of external focus are consistent across age groups, benefiting children, adults, and older adults alike.

Implementing Attentional Focus in Human Factors

The application of attentional focus research in human factors holds significant promise. IFUs in the medical device industry could benefit greatly from incorporating these findings. Let’s reconsider the surgical robotic suturing example. Instead of instructing users to “rotate your hand and wrist,” instructions could be revised to “rotate the surgical instrument,” emphasizing the effect of the movement rather than the body or the movement itself. This change in instruction would likely improve the capabilities of that surgeon to perform their suturing task, such as their speed, accuracy, and rate at which they improve their performance.

Conclusion

Integrating attentional focus research into human factors could transform the way we design instructions and train individuals across various fields. Considering how we direct attention can lead to significant improvements in performance and learning. As human factors professionals, it is crucial to explore and implement these insights to optimize outcomes and enhance user experiences. The next time you design an instruction, remember a single word can help unlock human potential.

For more resources on Medical Device Human Factors please check out our blog and YouTube channel.