Professional Tips for (Graduate School) Success

Professional Tips for (Graduate School) Success

The goal of this book is to provide you with all the tips, tricks, advice, wisdom, strategies, suggestions, recommendations, counsel, and information – did I miss any? – that will help you overcome the barriers you will experience as you pursue your Master’s or PhD in the Human Systems Engineering program at Arizona State University.

And rest assured: it is not a matter of if you’ll encounter these barriers, but rather when, how much, and how frequently you will encounter them.

Although one of my early goals for this book was to provide you with an exhaustive list of “what if?” scenarios and ways to overcome them, the reality is that these pro tips are not a be-all-end-all guideline. An exhaustive list would be, well, exhaustive. It would take too long to read. It would inhibit your ability to think about the problems between the lines. Many points wouldn’t make sense until you encountered them first-hand. Etcetera. And my guess is that many of you wouldn’t read it. And who could blame you? Instead, my revised personal goal for this book is to help you identify the nuances of your learning experience and detect when, where, and why you should apply one or more of these pro tips.

One point that will be emphasized in this book is that your learning context (e.g., your environment, relationships, peers, and resources) will have a profound influence over your graduate school experience. You should not take these pro tips as the solution to all the problems you’ll face. You’ll need to tweak and bend, pry and pepper things in as you go.

This collection of pro tips is intended to serve everyone – new graduate students, seasoned graduate students, and even the occasional faculty member too. One reason that I feel this is possible is that this is an ever-expanding, ever-updating, ever-Everest collection of input from students and faculty at ASU. It is a family-style platter of ideas filtered and condensed into a cold-brewed brainy beverage that you can sip on and enjoy, or chug until your heart’s content (cream and sugar cost extra).

With this community-based approach in mind, remember to continue sharing your ideas. Share them with me, your peers, and your faculty members and mentors. This information becomes increasingly valuable the more you contribute. As you will see in the coming pages, it doesn’t matter how big or small your pro tip is, if it has helped you in some meaningful way, it will most likely be useful for others to try as well.

Let’s jump right in —-

1. “CMD+F” & “CTRL+F” are your friends

1. “CMD+F” & “CTRL+F” are your friends

One great advantage of having most – if not all – of your reading list in journal article format is that this information is almost always delivered as a PDF. Most PDFs — but not all, — that you will be asked to read will have searchable text fields. Which means that you can use “ctrl + f” on Windows or “command + f” on Mac to search the heck out of that article.

After learning about this functionality, the average simpleton thinks of one thing: “now I can just search for the answers to my homework questions and be done in like 5 minutes!”.

Yes and no.

Yes, all ethical rationales aside, you technically can do that. But the overwhelming majority of your homework questions will not be the familiar “skill and drill” format that made it so easy to get through your undergraduate classes. And even if you do get the occasional question like this, you will undoubtedly have to answer a follow up question that takes substantive thought and reflection. Sorry!

So, why is this tip helpful?

As you conduct your literature reviews, you can use this feature to search for keywords that tie back to your reading questions. For example, if one of your questions is, “what was the intended purpose of this article?”, try searching, “purpose of study” — or something similar. If one of your question is, “what was the effect size reported in this study?”, use the search feature to look for terms like, “effect size”, or even, “p =”. Both of these search phrases should narrow things down to useful areas in the results section.

Once you understand the purpose of an article, it’s often much easier to gauge whether or not that article will address your reading questions. If not, move on. If it looks promising, try another search using different keywords that pertain to your reading questions. Unique phrases, terminology, authors, and years are all usually fair game too. After you acclimate to some of the key authors in your field, you’ll know to search their names in related articles to determine how well the two or more journal articles overlap each other.

2. Avoid bedazzled, ostentated, flummoxed words.

2. Avoid bedazzled, ostentated, flummoxed words.

Just in case you didn’t understand the title, here’s the quick and dirty of it:

Avoid using complex words.

As a graduate student, you have a three-part dilemma to resolve as your write your thesis or dissertation. First and foremost, you need to communicate what you did and why you did it. Second, you need to convince your reader that you are credible and the work you did is virtually air tight. Third, you need to leave just enough language in there that conveys your research is not the be-all-end-all answer to the problem – after all, your results only “suggest this”, they never ‘prove this’.

Each of these “needs” can feel like they are constantly at odds with each other. For example, if I leave too many “may-s” and “might-s” and “possibly-s” in my writing, it undercuts my credibility. But if I don’t hedge some of my language, I run the risk of implying that my research is the solution.

For what it’s worth, this dilemma is universally experienced by graduate students and faculty members alike. However, a key difference between an inexperienced graduate student and a veteran faculty member is how quickly each one is capable of honing in on that balancing act. The former struggle with it for months at a time, writing themselves into corners, remaining too reluctant to use the “delete” key to get themselves out of the whole mess. The latter may struggle with it from time to time, but know what pitfalls to watch out for as they go. This, of course, takes years of experience to learn. Years of failing and starting over. Years of frustration and booze. And while time is one of the resources graduate students have in high supply, you don’t have that much time.

Sooner or later you will feel the need to get unstuck. And the following bright idea will hit you: “what better way to resolve all three components of my dilemma than to “smart talk” my way out of it!

Avoid this temptation like the plague.

Words like “pontificate” and “superannuated” and “multifarious” sound brainy. In fact, they are brainy. But they are also downright unnecessary. Replace “pontificate” with “lecture”, replace “superannuated” with “obsolete”, replace “multifarious” with “numerous”. In almost any case you feel yourself reaching for the thesaurus to find a different way to say something, stop for a moment and ask yourself why. What’s wrong with the word you were thinking of?

3. Know the characteristics of your participants

3. Know the characteristics of your participants

If your thesis or dissertation research is completely and utterly dependent on a couple dozen sleep-deprived, hung-over, uninterested, perpetually confused undergraduate students with an umbilical cord-like attachment to their smartphone – you are in for a rude awakening.

This isn’t to say that all undergraduates make for “bad” participants. If we made that claim, it would call into question about 50% of the research conducted in the fields of behavioral sciences. The take away point here is that undergraduate participants are okay, but like any population that is receiving little immediate value out of the research experience, they have their limits.

At least in the User Experience industry, it’s not unheard of for participants to be paid $100 – $200 for an hour of their time. Not bad, considering all they have to do is mess around with some new gizmos and slop down an answer or two on a questionnaire. But in the realm of academia, large payments like this are virtually non-existent. There just aren’t the dollars to support it. And not surprisingly, the level of undergraduate enthusiasm for research often matches its rather underwhelming means of compensation.

Remember though: you need them, and they need you. It’s a symbiotic relationship, really. Likewise, there is also an ebb and flow to this relationship as well. Kind of like a type of supply and demand.

At any given point in the semester, there could be an influx of studies available to undergraduate participants – one, of which, might be yours. Good for them, bad for you. The opposite can occur as well – the student checks on SONA, and look, your study is the only one with available time slots. Good for you, bad for them.

Whatever the case may be though, always, always, always show appreciation for your participants time and attention. Even if it didn’t take all that much time, or even if they didn’t pay all that much attention. They still did something that helped you out, so appreciate the value they did provide.

Some sessions you will have really bad participants – people that make you want to pull your hair out and smash your face into the rest of your face. Other sessions you will have really good participants – people that are genuinely interested in your research and try their best.

For better or worse, both groups represent your population. To think that the rest of the world operates any differently is just plain silly. Your role as a researcher is larger than your research – you are shaping these students’ impression of what research is and why it matters. Show them a side of science that will get them hooked.

When you are in the planning phases of your research, try to think of who your participant population will be. What do they want, what do they want to avoid, what do they value, and what value do they see in your research? The answers to these types of questions should help you gauge what types of results you can expect to get out of your study. Also, anticipating these limitations can also help you figure out how to organize your research questions so that one or two bad eggs won’t spoil all of your results. Whenever possible, design your study in ways that one or more research questions are not entirely dependent on all the responses a participant provides. For example, even if a “bad” participant provides things like their demographic information, that may still be useful in helping you answer some other research question.

4. Keep a related theme among all of your class projects.

4. Keep a related theme among all of your class projects.

Each of your classes will often require you to complete a culminating research proposal that takes into account the various concepts you’ve learned throughout the semester. This will be especially true in your Research Methods class (SMC520), and your Advances in Theoretical Psychology classes (PSY560).

Whenever possible, use these class projects to make progress on your thesis or dissertation research. For example, find journal articles that parallel your class topics as well as your thesis research topics. This will not only cut down the number of journal articles you will potentially read, but also forces you to think somewhat differently about your thesis research. Furthermore, since this is a class project, you will get feedback from professors that may not be apart of your research committee. You can use this feedback to inform the research that you will eventually conduct for your thesis.

Think of this “double-dipping” approach as a conceptual pilot for your thesis or dissertation research. You’re weeding out all the kinks and snags before it is technically time to sign up for your thesis credit hours.

One goal to keep in mind with organizing your projects in this manner is that your efforts should afford more than a 1-to-1 output. Meaning, the effort and resources you invest in a project should have short-term, mid-term, and long-term benefits – not just one benefit.

Successful businesses do this all the time. For instance, the fast-food chain, Chick-fil-A, recently started an aggressive marketing campaign to get their app into the hands of their customers. They incentivized customers to download their “Chick-fil-A One” app by offering up a free sandwich that customers can claim during their next visit. On one side of the equation they’re spending tons of hours developing, testing, hosting, and fixing their app – not to mention, eating the cost of all that free food.

So, what do they get out of it?

By convincing customers to download, install, and sign-up with the “Chik-fil-A One” app, they get your name, email address, age, gender, and zip code. These data are virtually priceless for a company to know. It helps them tailor their advertising, it helps them know what markets they are performing well or poorly in, it helps them know who their customer base is (e.g., age, gender).

But that’s not all. This simple app covers a lot more ground than that.

They now have customer’s email addresses, which means they can send out promotions and reminders to thousands of people with virtually no cost on their end. Additionally, the fact that their app has a little icon on their customer’s phones acts like a constant reminder in itself — “go to Chik-fil-A”. When customers see that tiny Chik-fil-A logo, their mouth waters a little.

Pavlov would be proud.

All of this is accomplished before ever getting into what the app actually does once you open it. There are tons of other “double-dipping” strategies nested away in this app itself. If you now have a new found respect for Chik-fil-A, don’t waste your time thinking they are a bunch of smarty pants. Every business out there that offers an app is doing this exact same thing.

However, what you should do is take a note out of the deep fried, breaded book of the “Chik-fil-A One app” and think of ways to do some double-dipping of your own… just not the deep fried type though.

5. Hey, Dummy. It takes time to learn you’re a dummy. So quit acting dumb, dummy.

5. Hey, Dummy. It takes time to learn you’re a dummy. So quit acting dumb, dummy.

Learning takes time. Sometimes you read and read and read and read and then you think you have it and know what you’re taking about. Then, you read a little more and realize you don’t know nearly as much as you thought you did.

The pattern described a second ago is experienced by almost every graduate student to some extent.

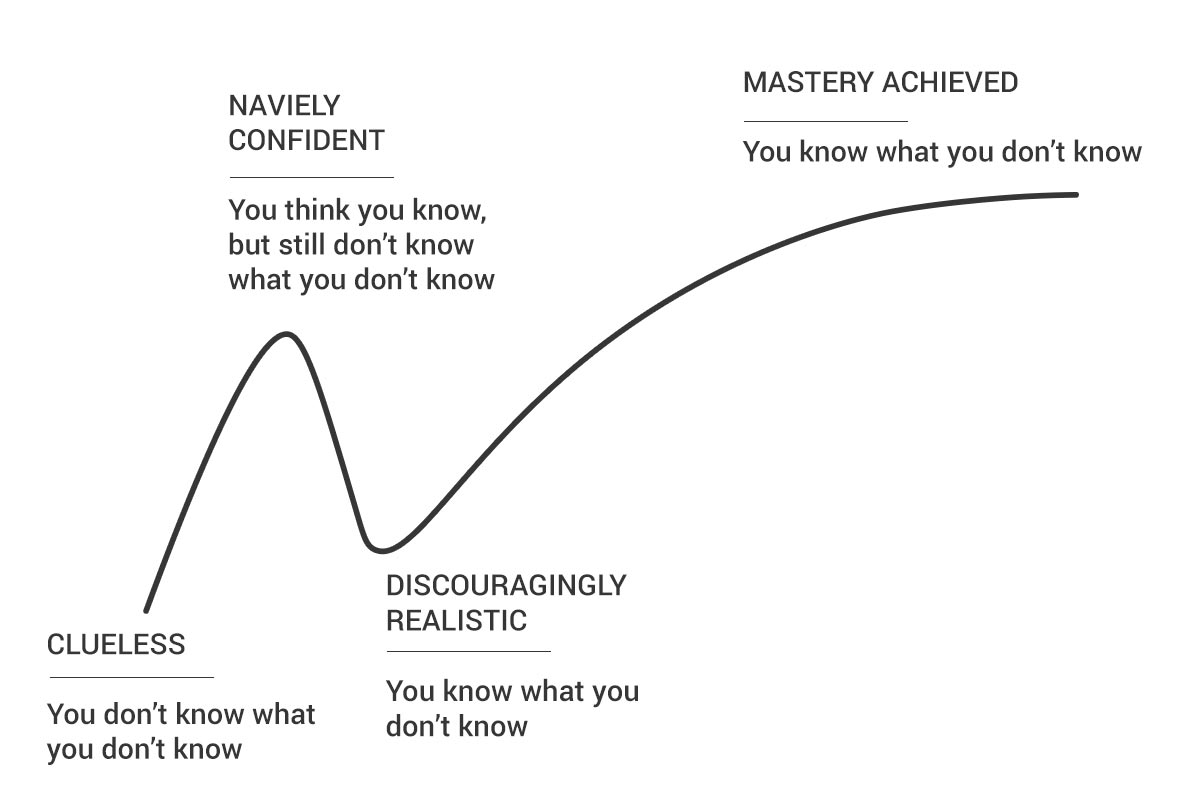

As an undergraduate, you typically get your diploma somewhere between “clueless” and “naively confident”. Once you get into graduate school, you’re feeling good. You know more than the average bear and you have the GPA to back it up.

Then, you realize that you will only be reading journal articles from here on out. No more book chapters, no more SparkNotes, no more condensed note sets that the professor put together after hours and hours of unappreciated work. Believe it or not, this realization is a step in the right direction. You’ve reached what is referred to as, “discouragingly realistic” – you know what you don’t know.

The more you continue to read and learn, the further you will climb out of the “discouragingly realistic” phase, and up the slope toward, “mastery achieved”. At the domain-level, this will take years and years to reach. It might even take your entire career. But at a topic-level (e.g., what you need in order to pass your thesis or dissertation), this is much more manageable within a few years.

The bigger thing to remember is that graduate school isn’t about making you an expert in this field. Despite a piece of paper saying you have a “Mastery” of Human Systems Engineering, what you actually have is a solid foundation to continue learning.

If nothing else, graduate school should teach you how to learn and develop on your own. And if you’re lucky, it will inspire a lifelong passion to continue learning. This passion is something that transcends domains – you could take these lessons and go into law, or medicine, or library sciences and be equally successful.

6. Invest in the right type of printer.

6. Invest in the right type of printer.

If you read an earlier pro tip about how many journal articles you will read as a graduate student, you probably reached the conclusion that you will also be printing a ton. Just in case you missed it: expect to read between about 275 – 400ish journal articles for every calendar year you are a student at ASU.

Your average journal article will be about 10 – 15 pages, not including things like the article’s citation pages. Some will be shorter. Some longer. Based on the number of journal articles you should expect to read each year, that puts your total page count right around…

2,740 – 5,880 pages… per calendar year.

Okay, just to put this into perspective a little more, your standard copy paper is made from a mixture of softwood and hardwood trees – which, on average, are about 40 feet tall, and 6 – 8 inches in diameter. One (average) tree produces approximately 1.66 cartons or 16.67 reams of piney fresh, 8-1/2” x 11”. One ream of copy paper contains 500 sheets.

After some simple mathing, that’s 8,335 pages of copy paper per tree. Which means, by the time you’ll graduate from this program with a Master’s degree, you’ve read through almost an entire tree. And if you’re graduating with a PhD, well… just be sure to plant a few trees afterwards.

All of this nonsense isn’t some plea to “be a green devil”, or to reuse your towel when you stay at a hotel. The point is to show you that if you decide to print off each and every one of your journal articles, you will go through a ton of paper — figuratively and literally. And with all that paper, you will also need a bunch of ink.

One of the best investments I made as a graduate student was to buy a monochromatic, duplexing, LaserJet printer. In layman’s terms, that means a printer that prints only in black-and-white, automatically prints on both sides of the page and uses toner instead of ink. The one I bought was just south of $100 and is still working just fine.

What made this printer worth this price?

The main cost of printing is replacing the printer’s toner or ink cartridge. Most InkJet printers use regular yield cartridges. Which means you might get a few hundred pages printed off before you need to buy a new cartridge. The other downside to InkJet cartridges is that you typically can’t refill the cartridge at home. You often need a special device that opens it up and all that jazz.

On the other end of the printing spectrum, you have LaserJet printers. These are what you usually find in an office setting. Their sole purpose is to print tons of paper quickly and cheaply. To accomplish this, many LaserJet printers forego the color cartridges and rely only on black “toner” – a very fine, black powder that stains your carpet and makes you lose your apartment’s security deposit. Unlike most InkJet cartridges, LaserJet cartridges are often, “high yield”. Meaning, you can print off 1,000 – 2,000 pages before having to replace anything.

Toner is usually a tad more expensive than ink. But you get far more out of it before having to buy more. More importantly, though, toner cartridges are often designed for your average office employee to open it up, empty it, and refill it with new toner. Best of all: refilling the toner yourself costs about 75% less than purchasing a whole new toner cartridge. For example, my toner cartridge costs a whopping $3.36 to refill after I print off about 2,000 pages.

Think about your reading habits before you buy a printer. Do you prefer to have a tangible, hard copy of your journal articles, or are you alright with reading them on the computer? If you lean toward the former option, also consider whether you would like to print from your phone or other smart devices. Many LaserJet printers today offer ePrint and AirPlay print compatibility.

A complete version of the ebook is available here: Pro Tips for Graduate School Success